I grew up in a growing suburban village at the end of the metro bus line, with woodlands and farms and streams nearby. My folks were delighted to live in a community of new houses and families with young children. Of course, we loved the place as kids, and as adults my wife and I selected for our home and family a setting with both nearby urban amenities and plenty of open space.

When I was young, the city was a foreign and complicated place, and I saw it as through the eyes of a tourist in a distant land. In December Mom would take us on the bus to go downtown for Christmas shopping and we would be dazzled by the big stores and the lights and the bustle. That was pretty exciting, until the big, new suburban malls were built. We would also go into town to visit the Grandparents and the cousins; who lived in little houses in various aging, transitional neighborhoods where the neighbors were so close and yet so different. That was unfamiliar, and a little scary.

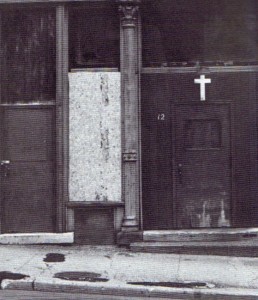

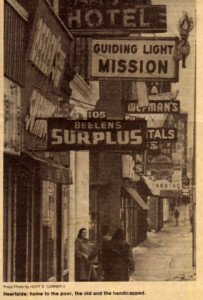

I was in my teens in the late 1960s when American cities erupted in riots, and we came to see the cities as places to fear, or at least to be concerned about; or, to put a human face on it, to be alternately concerned about and afraid of people who lived in the city. In college I studied sociology and put myself squarely in the urban mix, volunteering in a “skid row” outreach program to the poor and homeless, the mentally ill and the drug abusers. Our community center was just two blocks from where Mom used to take us Christmas shopping, the stores now empty as people shopped at the suburban malls. I didn’t see the city as a place of wealth, a place where wealth was made and exchanged, a place that represented the investment of previous generations. I saw it as a place of need, a place of deterioration and decay. That seems to have been the national consensus about cities.

My bride and I moved into an older city neighborhood and I started working for non-profit community development organizations, rebuilding old homes and commercial buildings. During those years I came to see the city as vibrant, vital, and fascinating; rich in culture and architecture and infrastructure; full of good, hardworking people who had created stable, supportive “urban villages” within the larger cityscape. Yet for years many areas of our cities languished in “disinvestment,” physical blight spread, poverty increased and jobs went away. And during those same years the farms and woodlands of my boyhood community were transformed into residential “bedroom communities” accessed by highways and serviced by chain stores with big parking lots.

Over time, our national consensus about cities has been changing. Suburban living is still as popular as ever, and I have no reason to belittle it. But perhaps we are reaching the natural limitations of the growth of automobile dependent suburban rings, and we question the ever-outward expansion, (sometimes called “sprawl.”). Perhaps we recognize that the quality of suburban life is dependent on having both a vibrant, economically healthy urban core and nearby natural, rural areas, like my childhood suburban community. Perhaps we are rediscovering the value of cities and living in urban communities. For whatever reasons, Americans are re-discovering their cities just as surely as they lost interest in them 40 years ago. Young adults come to the city for the bustle, the social opportunities, and the diversity. “Empty-nest” older adults come for the cultural opportunities. People of all ages are coming for the jobs, as some businesses choose to relocate downtown.

My observations and experiences with urban growth, disinvestment and rebirth came into new perspective for me a few years ago, when I attended a lecture by John O. Norquist, (who was mayor of Milwaukee from 1988 through 2003,) and read his book, The Wealth of Cities, (1998.) Norquist looks at the history and role of cities, explains their natural advantages, and goes into some detail to discuss state and federal policies (1930s – through mid-1990s) that damaged the cities, and outlines ways in which cities can lead “an economic and cultural renaissance.”

Here are a few key points from the opening chapters of The Wealth of Cities:

- Natural Advantages. “Their (the cities) physical properties –scale, proximity, and diversity – are their chief advantage. The benefits that accrue where large numbers of diverse people live and work closely together include the most efficient results in transportation, labor exchange, consumption, capital allocation, culture, and education….You can build a city on its natural advantages; its efficient proximity and density, its processes and markets, and its extraordinary capacity to promote the success of its citizens.”

- Density and the Marketplace. “Cities result from trade, from the interaction of people through markets….Unlike counties, states and nations, most cities were formed as marketplaces. …cities were created by human interaction and market forces, not by government… Cities form as people gather together. Large numbers of people living close together communicate, work, trade, sell, buy, and specialize easily and thus to a greater degree than do people who live far apart from one another.”

- Efficiency, Profit, and Culture. “The efficient proximity of people in cities and the consequent ease of interaction unleash processes that build civilization. Specialized labor results in leisure time, which can be devoted to creating art, music, religion, and culture; concentrated capital, which essentially is wealth, fosters greater productivity… People living and working together bring about the mix of communication, supply, demand, invention, creativity, and productivity needed to fuel enterprise and generate profit. And only if profit exists – whether it is the working person’s small savings or the giant corporation’s large surplus – are resources available to advance art, education, and culture.”

In The Wealth of Cities Mr. Norquist lays out the various causes and interactions that led to the decline of the American City in the last half century, and it resonated with me because it is a history that I witnessed and lived through and that shaped my early career choices. Here is his summary (the bold type is by me):

“At the end of World War II cities suddenly became expendable. Communities with porches, sidewalks, streets, blocks, neighborhoods, and grand public spaces were largely abandoned and replaced with the now-familiar collection of strip malls, cul-de-sacs, and sprawl. But it wasn’t only design that hurt U.S. cities. As the cities deteriorated physically they also lost their sense of purpose. The dynamic urban markets that drove commerce and served as ladders to prosperity for millions of immigrants in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries began to be viewed as the problem, even the cause, of poverty. The city as incurable disease replaced the city as platform for opportunity. Remedies intended to revitalize instead overwhelmed the productive assets of cities. Social services, public housing, welfare schemes, and other efforts at artificial respiration became bigger and more important than the cities and their people. Instead of being rescued, U.S. cities were victimized by federal interference, and their status as victims was institutionalized.”

In his book Mr. Norquist also gives his vision and suggestions for the American cities of the twenty-first century. I’ll leave further reading to you. Mr. Norquist is on the board of the Congress for the New Urbanism, which promotes “walkable, mixed-use neighborhood development, sustainable communities and healthier living conditions.” More information available at www.cnu.org.

In my lifetime I have been able to observe what I estimate is three-quarters of a full cycle of the decline and reinvention of the American city. Today I can show you, amid restored buildings with condos and offices and busy restaurants and boutique shops, other commercial buildings with vacant upper floors that were vacant before I was born. But there are fewer and fewer of these buildings, and I expect that in ten or twenty years these buildings will be full again. For many reasons we are now starting to recognize our cities, our existing built environment, for their opportunities, not just their problems. We are recognizing that the prosperity of cities is integral to our prosperity as a nation, and to the quality of life in suburban and rural areas.

I’m not a developer, a politician or a civic leader. I’m a technician, a builder and manager. My experience includes all kinds of projects. But I find the adaptive reuse of older urban buildings particularly rewarding because there is often so much opportunity in an older building or even a vacant urban lot. There is so much value – wealth – waiting to be tapped there. Not that adaptive reuse is necessarily less costly than new construction, sometimes the opposite is true. The value is in the density, the community, the proximity, the traffic patterns, the public infrastructure, the urban market place. There is value in keeping the old buildings out of the landfill. There is value in not building in an undeveloped area; in keeping natural areas nearby while maintaining our existing built areas. There is value in keeping the urban fabric whole. There is value in the history and architecture.

I enjoy serving clients who want to live, work or have fun in our urban environments. I enjoying exploring opportunities with them and hearing their vision. It is rewarding to bring my experience, skills and knowledge to their project and help make it a reality. Today I can take you to dozens of homes and businesses where that has happened, maybe tell you a bit about what the place looked like when we started the project, and tell you about how the neighborhood has changed. We can see the wealth and vitality of the city in action. It’s great to be part of that.