In plain English you might say that I have always been an “old building guy,” the builder who was always working on some old building. I would prefer to say that I am an “adaptive re-use specialist,” which might be an inflated term, though I would like to think that after 50 years of doing this I have learned something about how buildings age, survive or fail, how human interaction with buildings changes them, and how a building or space can be put to a new purpose, perhaps one that the original designers and users never imagined. I’ve watched buildings and neighborhoods in our community for some decades now, and I find the evolution, repurposing, and change fascinating.

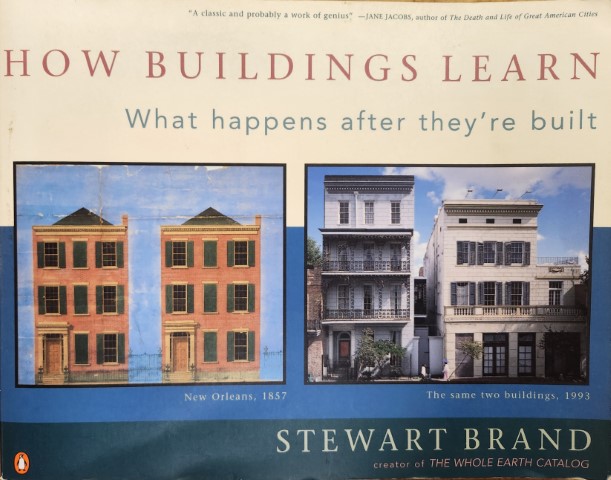

One of the most instructive things I’ve read on this topic is the book How Buildings Learn, What Happens After They’re Built, by Stewart Brand (Penguin, 1995.) Brand says that rather than consider a finished building in “space,” as architects and builders do, he wanted to look at the buildings in “time,” to consider what happens “when the users take over and begin to shape the building to suite their own real needs.” I strongly recommend the book, and also viewing the BBC documentary of the same name (1997.) The documentary is in 6 parts (3 hours total,) and is available on YouTube. Since many fine reviews and comments on the book and documentary are available on-line, I will not go into depth here, but rather just touch on a few points where the book intersected with my experiences and thoughts.

In another essay on this site I talk about the Freeman House, and how touring that home opened my mind to the ideas of a building as art and the possibility of design. As much as anyone I enjoy a building that is artistic and inspirational. But my experience makes me agree with Brand when he suggests that the “best” buildings; that is, the best for people and communities over time; are those that have standard and familiar designs, are made of well-understood, readily available and moderately priced materials, and are easy to modify. Grand and artistic buildings may be fun at first, but they can be hard to maintain and harder to adapt, and may become a drag on the community, while simpler buildings lend themselves to innovation and economic growth. Consider also this: when the market favors new construction (residential and/or commercial), existing buildings often get less re-use, less maintenance, and those buildings and their communities may suffer. In times (like recent years) when new construction is depressed, we pay more attention to keeping our existing buildings viable, to re-purposing and rehabbing our existing stock. And which buildings and communities are improved first? Usually those that are simple, familiar, and can be addressed most economically.

Over the years I have had opportunity to work with several fine architects who understand adaptive re-use and work collaboratively, and have met some who didn’t get that at all. So I had to smile when I read Brand’s critique of certain well-known architects and the profession. “What would an architecture student learn,” he asks, “by following a remodeling contractor through a series of jobs? How about following a building inspector around for a few weeks?” Brand suggests that we would do well to develop a science of building behavior, to look at “the whole tangle of relationships that make a building work or not… Without that kind of corrective feedback a building can’t thrive. Neither can the building professions and trades.” For years I joked that I practice “forensic carpentry,” that in the process of taking apart and renovating an existing building we discover much about its history, usually by observing failures: we see what designs have succeeded or failed, we see the results of poor construction or neglected maintenance, of abuse or amateurish “re-muddling.” Sometimes I lament what I see as the decline of skill, craft and concern in the building trades, driven by a desire to make things less costly…at least in the short term. Other times I am equally frustrated by buildings that were “over-built,” that are static, that are difficult to deal with once their first purpose has expired. We would do well to try to find a balance, creating buildings both adaptable and sustainable.

I will close with a few words about “sustainability.” That’s an important term these days, sometimes associated with “environmentally friendly,” and low energy use, perhaps “alternative energy,” and I sort of like the term “high performance.” I’m in favor of all those things, I have hands-on experience with them, I have had the U.S. Green Building Council’s LEED training and agree with USGBC on most issues. But I often feel that the term “sustainability” is used too narrowly in common discussion, as if only new buildings (perhaps meaning buildings with solar panels and wind turbines) will be sustainable. I believe that the “greenest” buildings on Earth are the ones already built; that they (and their community infrastructure) represent a store of resources and energy (including human energy) that will serve us well; that recycling a building is as important to our future as recycling paper, bottles and cans. We now talk about “lifecycle analysis” for products, even new buildings, to look at how their materials and components can be reused at the end of the product’s life. That’s good, but we could do with far more understanding of how whole buildings, the buildings already built, the buildings that are old and obsolete, have already performed through time, interacted with their occupants and community, and how we can, in our adaptation of buildings to our current uses, make them amenable to future adaptations.